This article is part of The Hivemaker’s Code series:

- Article 1: Introduction

- Article 2: How do Ecosystems Grow?

- Article 3: Cooperating on Blockchain

- Article 4: The Satoshi’s Dream

- Article 5: Anonymity in the Cryptosphere

- Article 6: Democracy and Decentralization

- Article 7: Is Net Neutrality Important for Blockchains?

- Article 8: Why Interoperability is the Bedrock of Digital Freedom

- Article 9: The Way Forward

How to Manage Commons in Digital Ecosystems?

Authors: Oliver Lukitsch, Michal Matlon, Gregor Žavcer, Thomas Fundneider, Markus Peschl, Lena Müller-Naendrup

How do we deal with something that’s neither privately owned nor managed by authorities on our behalf? Something that everyone, as well as no one, owns. In other words, how do we manage “commons” so that their tragedy doesn’t become a reality?

Commons are widely shared things such as goods, small-scale resources like irrigation systems, as well as more abstract and large-scale resources such as a shared language or a climate ecosystem.

The issue of who takes over responsibility for something that no one owns but everyone uses has occupied political, philosophical, and psychological debates for centuries. What drives human cooperation in using the commons? And in crypto, can we collectively pursue goals in anonymous groups without clear institutionalized guidance and ownership?

Social psychologists, for example, say we have mental biases shaping our cooperation. For instance, we are more likely to cooperate with people we are related to, who we think belong to the same group as us, or who look familiar to us.

On the other hand, economists advocating for Rational Choice Theory have claimed that our actions and decisions are always motivated by self-interest, personal preferences, and benefits.

The question of human cooperation has witnessed a revival in light of the explosion of the internet. The commons evolving within the digital sphere are even less tangible and more far-reaching than what we have dealt with so far.

Online networks and platforms stretch over ever-growing communities of diverse people dispersed around the globe. We connect with people we have never met and we cooperate with them extensively online. We overcome our alleged biases and together create wonders such as Wikipedia, which hosts human knowledge created purely on voluntary terms.

The question remains. How can we cooperate sustainably in times of increasing digital anonymity? How do we build collective trust, counter free-riding, and use shared resources responsibly? How can we replicate the success of Wikipedia?

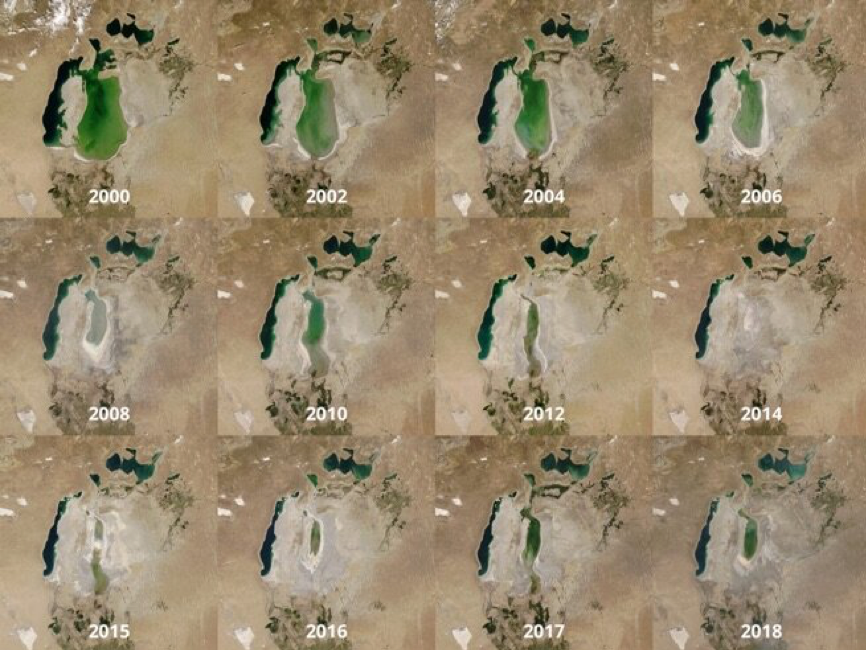

The Depletion of the Aral Sea: A Tragedy of Commons

Let’s come back to the topic of the commons. The depletion of the Aral Sea, once the fourth-largest lake in the world, perfectly illustrates how a shared resource falls prey to a tragedy.

Between the 1960s and 2018, the sea’s surface decreased by over eighty percent, leaving behind a barren, toxic, and inhospitable desert. Millions of people and fish lost their home environment of 54 000 square kilometers of freshwater. The story of the Aral Sea is an environmental catastrophe, but even worse, it’s a human-made one. And some might claim it’s a Tragedy of the Commons.

Image: NASA Goddard Space Center, https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0/

Image: NASA Goddard Space Center, https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0/

The Aral Sea’s freshwater has been used for fishery and agriculture by Kazakhstan and Uzbekistan farmers for centuries. Until the Soviet leaders initiated a five-year plan of water-intensive cotton farming in the desert of Uzbekistan, the lake provided a perfectly healthy ecosystem.

As the Soviet project involved redirecting two of the largest water-supplying rivers to use for irrigation purposes, the Aral lake rapidly lost a thousand cubic kilometers of freshwater to the cotton industry of the Soviet Union. The sea is a common water resource that used to be accessible to everyone. However, as one stakeholder overused the water resource, the lake’s value for others declined massively.

So what does the Tragedy of the Commons mean? In 1968, the socio-biologist Garrett Hardin published a Science article titled “The Tragedy of Commons.” The article stated that the finite nature and open character of shared resources would inevitably lead to overuse and depletion. He wrote:

“Therein is the tragedy. Each man is locked into a system that compels him to increase his herd without limit - in a world that is limited. Ruin is the destination toward which all men rush, each pursuing his own best interest in a society that believes in the freedom of the commons.” (Hardin, G., 1968)

According to Hardin, without top-down interventions and governing authorities, the self-driven individuals who use common resources will eventually be confronted with a threefold problem.

The first issue is overuse. If a shared resource is finite, one person using it decreases its value for another person. Second, as the resource is open by default, no one is excluded from its use. This makes its monitoring and governance difficult. And last, any problem increases in complexity in a large community. Decision-making is much easier in local and intimate communities compared to anonymous, large groups.

The symptoms of those three problems are so-called “free-riding individuals.” Whenever an individual can’t be excluded from a community resource, they might be seduced to stop contributing to it or regulating their behavior. And the only solution to this tendency is to devise an effective way of communicating, monitoring, and sanctioning within the group.

Ostrom’s 8 Principles for Managing Commons

Hardin’s Tragedy of the Commons can provide a simple explanation for all kinds of social dilemmas: traffic jams, overfishing of oceans, or dirty public toilets. Nevertheless, there are examples of successful, self-governed commons and collective management systems, like the Acequias in New Mexico, sustainably managed by ordinary people for generations.

And one scientist decided to find out what stands behind thriving communities that use their resources responsibly. In her Nobel Prize-winning research, Elinor Ostrom concluded that the reality of human cooperation in using commons might not be as grim as Hardin has sketched.

Based on her decades-long research of well-managed commons, Ostrom strongly believed that groups are capable of avoiding the tragedy of the commons without requiring direct top-down regulation. Based on her findings, Ostrom created a list of eight principles for managing commons that can be applied both in the physical and digital worlds.

- Commons require clearly defined boundaries: It should be clear who has access to commons, under what conditions, and where they begin and end.

- Governing rules should match local needs and conditions: Commons are context-sensitive, so people in the community should create the rules.

- Participatory decision-making: People affected by rules are likelier to adhere to them if they have participated in defining them.

- Monitoring the commons systems and community: The community must develop a system for checking and monitoring the community members’ behavior.

- Graduated sanctions for rule violators: Commons work best when they include systems of warnings, fines, and informal reputational consequences before banishing members from the resource for good.

- Providing accessible, low-cost means for conflict resolution: Members should be encouraged and enabled to bring up any issue so that problems can be solved by mediation rather than ignored.

- Other authorities should recognize the commons: Commons can only sustain themselves if their rules are recognized as legitimate by higher authorities under which the community falls.

- Commons should be embedded in larger systems: Many commons require large-scale cooperation and widespread responsibility to be managed successfully.

By outlining these principles, Ostrom illustrated how commons could be successfully managed and provided in-depth insights into why some groups fail to govern themselves. In line with Hardin’s reasoning, Ostrom argued that communication and trust constitute critical challenges to group-based governance of shared resources.

Suppose there are neither efficient ways to monitor social behavior nor means to introduce sanctions in case of a dispute. In that case, the commons fall prey to their substractibility and openness. Free riders will then benefit from the community, and the collective overuse might initiate a tragedy.

Ostrom’s principles particularly highlight the need for communication within and beyond the community, the centrality of participatory decision-making processes, and transparency among the community members and processes.

Blockchain: A Contested Common

So how do these principles translate into the digital world? We could say that the blockchain is a new kind of shared resource. One which might bear the potential to circumvent the tragedy of the commons by embodying principles similar to those Ostrom suggested.

So how do these principles translate into the digital world? We could say that the blockchain is a new kind of shared resource. One which might bear the potential to circumvent the tragedy of the commons by embodying principles similar to those Ostrom suggested.

Generally, the blockchain constitutes a technological infrastructure for applications such as cryptocurrencies, decentralized data storage platforms, and smart contracts systems. Simply said, blockchains are continuously growing, immutable ledgers that contain information about transactions. As they are digital and online by nature, blockchains generally have three qualities:

- Blockchains are decentralized, as the ledger containing information is not centrally stored but distributed among all the participants.

- Blockchain ledgers are accessible to anyone participating in the system.

- Blockchains are immutable, holding that already existing information on the blockchain can never be deleted.

In addition, they are run by a distributed verification system (like “mining”), through which connected computers verify transactions added to the chain’s final blocks. Joining the validation process is then rewarded, usually with a virtual currency the given community uses. The seemingly simple principle of a decentralized, non-exclusive system that rewards cooperation posits a promising scenario for the common’s resources dilemma.

The Immunity of the Blockchain

The commons’ biggest challenges surround their susceptibility to overuse due to lack of trust and complexity of communication in large-scale social systems. In contrast to other commons, blockchain-based commons, assuming infinite scalability, can be immune to these issues for multiple reasons.

Firstly, the overuse problem does not apply, as a blockchain community naturally benefits from its expansion. The larger it grows, the more value it creates. With every block added, with every new member joining the verification system, the amount of carried information increases.

Secondly, blockchain systems facilitate communication and promote complete transparency among all members. As others validate every contribution, all members are involved and informed about all processes occurring in the system. The necessity for trusting individual members is erased. Trust is instituted through the protocol, and the system guarantees monitoring of members’ behavior.

Thirdly, while scaling beyond the local level has been a challenge for common resource projects, blockchain commons benefit from a large-scale network effect.

Thus, applying blockchain technology to organize human cooperation might enable us to introduce new times of commoning. Times in which people from all over the world, far beyond the local scale, can jointly contribute to and benefit from one resource.

Blockchains in Light of Ostrom’s Principles

However, blockchain technology does not come with a risk-free recipe for commoning success. As Ostrom argued, the way a community cooperates depends on the nature of the shared resources and the conditions in which the community exists.

However, blockchain technology does not come with a risk-free recipe for commoning success. As Ostrom argued, the way a community cooperates depends on the nature of the shared resources and the conditions in which the community exists.

Within the blockchain community, there is a distinction between “radical” and “incorporative” blockchain proponents. While the former group attempts to rethink society and believes that a collaborative network of trust can stamp out the tragedy of the commons, the latter wants to incorporate blockchain technology within the existing systems, like traditional banking and communication networks.

For a successful commoning process, connecting people cooperatively via transparent communication mechanisms and providing easy access to information channels is essential. However, the blockchain boom, mostly centered around the growing cryptocurrency market, has been hijacked by an overzealous getting-rich mentality (“degens” in internet slang). A gold-rush game hardly anyone wants to miss out on.

Being a part of the hype often overshadows the desire to understand the underlying blockchain technology, resulting in an ever-growing community run by a small enclave of blockchain-skilled people. Especially in light of this rising unbalanced exclusivity, it is essential not to forget the blockchain’s original transparent and decentralized culture.

Insights such as Elinor Ostrom’s principles could serve as a guide for implementing blockchain technology as an infrastructure encouraging cooperation and trust. Many blockchain communities still struggle with governance, internal communication, decision mechanisms, and planning for future development.

These communities could use Ostrom’s principles as a framework for organizing themselves. Token-based membership models could clearly define a community’s members and borders, allowing for inclusive growth and providing incentives for cooperation. And smart contracts could allow for fast, decentralized decision-making processes. Projects like Giveth are already aligning themselves around creating purposeful social change.

We have used these principles as a model for decentralized, value-aligned ecosystems governance in our toolkit. Their potential goes far beyond pastures and irrigation systems as we enter the new era of global cooperation.

As we saw, overcoming the Tragedy of the Commons is not guaranteed. However, we believe that by learning from practices tested throughout centuries, new decentralized communities can successfully sustain themselves and use their potential purposefully.

Key Insights

- Commons are widely shared resources susceptible to overuse by individuals.

- Online networks create a new type of commons that needs to be managed.

- Elinor Ostrom’s eight principles distill how sustainably managed commons are run by their communities.

- Blockchain could help us overcome the commons’ issue through transparency by default and embedding trust in the system.

- Distributed, digital communities can embrace Ostrom’s principles to govern themselves and develop purposefully.

References

Broodje, Jaap. 2020. “The Success of the Commons.” The Connectivist (blog). November 17, 2020. https://theconnectivist.wordpress.com/2020/11/17/the-success-of-the-commons/.

Broodje, Jaap. 2020. “The Success of the Commons.” The Connectivist (blog). November 17, 2020. https://theconnectivist.wordpress.com/2020/11/17/the-success-of-the-commons/.

Dao, David. 2018. “Decentralized Sustainability - Beyond the Tragedy of the Commons with Smart Contracts + AI.” Enlivening Edge (blog). September 21, 2018. https://enliveningedge.org/tools-practices/decentralized-sustainability-beyond-tragedy-commons-smart-contracts-ai/.

Glantz, Michael H., Alvin Z. Rubinstein, and Igor Zonn. 1993. “Tragedy in the Aral Sea Basin: Looking Back to Plan Ahead?” Global Environmental Change 3 (2): 174–98. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/0959-3780(93)90005-6.

Hardin, Garrett. 1968. “The Tragedy of the Commons.” Science 162 (3859): 1243–48. http://www.jstor.org/stable/1724745.

Kuan, Lee. 2014. “Ostrom, Hardin and the Commons: A Critical Appreciation and a Revisionist View.” In . Ostrom, Elinor. 1990. Governing the Commons: The Evolution of Institutions for Collective Action. Political Economy of Institutions and Decisions. Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9780511807763.

Statt, Nick. 2018. “This Year’s SXSW Was All about Blockchain Dreamers, Cryptocurrency Scammers, and Everything in Between.” The Verge (blog). March 16, 2018. https://www.theverge.com/2018/3/16/17130532/blockchain-bitcoin-cryptocurrency-scams-fraud-sec-sxsw-2018.

Volont, Louis, and Walter van Andel. 2020. “The Blockchain: Free-Riding for the Commons From Potential Tragedy to Real Comedy.” In.

Williams, Jeremy. 2018. “Elinor Ostrom’s 8 Rules for Managing the Commons.” January 15, 2018. https://earthbound.report/2018/01/15/elinor-ostroms-8-rules-for-managing-the-commons/.

Discussions about Swarm can be found on Reddit.

All tech support and other channels have moved to Discord!

Please feel free to reach out via info@ethswarm.org

Join the newsletter! .